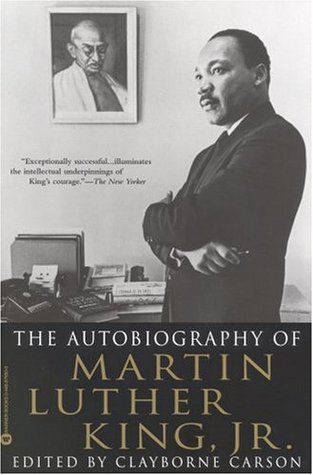

First published:- 1998

Star rating:-

Star rating:-

I had to keep reminding myself that it's not the civil rights movement I am rating and reviewing, because the spectrum of legitimate excuses, let alone justifications, which could explain the withholding of a star or two is rather limited. It comes as a kick to the gut every time a young, unarmed Clifford Glover or a Travyon Martin or a Michael Brown is shot for no valid reason and the realization sinks in that the process of integration which was initiated by Lincoln some 150+ years ago and furthered by Martin Luther is yet to reach its completion. So the essence of this book and MLK's doctrine of nonviolent agitation are now relevant more than ever.

In a way this is Martin Luther's own account of the movement he helped steer in a direction which not only sought to free an entire community from socioeconomic and political servitude but prevented America from becoming synonymous with the ultimate hypocrisy of all - preaching the infallibility of human rights abroad (by waging wars against Communist totalitarianism) but carrying on with its tacit agenda of institutionalized discrimination back home.

How the spirit of rebellion - which found expression for the first time with the Montgomery Bus Boycott in '55 (unwittingly started by Rosa Parks' act of denying her occupied seat to a white passenger) - trickled into the hearts of oppressed millions in Albany, Georgia, Birmingham, Alabama, Florida, Chicago, Boston, and Washington culminating in the passage of the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964, is recounted by King himself.

That aside, there's a brief autobiographical sketch patched together from the fragments of writings gathered from the Stanford University archive by Clayborne Carson. Excerpts from King's speeches (sometimes even the full text) also make appearances in between the accounts of all the non-violent movements of civil disobedience he gave leadership to.

To put it more accurately, this is less of an autobiography (since King didn't live long enough to write one) and more like a montage of every single written document or important oratory piece which King left behind. So lucidly written are these that Carson's work must have been reduced to simple editing and piecing together a coherent narrative out of the vast amount of material at her disposal.

And yet there are such glaring mistakes here which marred my reading experience. Consider this excerpt from King's personal writings after his visit to India in '59 which cemented his faith in the inviolability of civil disobedience as an effective tool to usher in socioeconomic and political change -

It's not Amniabad. In all probability, it's the Sabarmati ashram in Ahmedabad King is talking about, while the historic walk was to 'Dandi' - a coastal village in Gujarat (the state our present PM hails from). Not Bambi, the iconic Disney deer.

Even if it was a memory lapse on King's part or a sad apathy for geographical names, as a King scholar looking to publish a work of monumental importance Carson should have been more vigilant for inconsistencies such as the above, especially since Gandhi gets mentioned several times by virtue of his being King's role model.

(Some quick googling led me to the unhappy discovery that the Stanford archive still retains the unedited, therefore, incorrect information derived from the original sources. I can understand the significance of preserving King's writings exactly as he authored them but the insertion of incorrect facts diminishes the integrity of this work.)

Also occasionally 'Gandhi' is spelled as 'Ghandi'. (Aaarrrrggghhhhhh!)

In addition to these turn-offs, nearly all of King's speeches are so chock full of archetypal metaphor after metaphor that I felt it weakened the gravitas of the narrative. Perhaps, they would have been better off being included in shortened formats. The fact of God's mercy and benevolence being invoked (quite natural since King was a pastor) in every alternate sentence also served as an effective irritant. These are undoubtedly the primary reasons why it took me a whole month to finish reading this.

But these causes of botheration aside, there's plenty of good to be found in this compilation. Like the way MLK expresses his disappointment with 20th century capitalism in a letter addressed to his wife, Coretta -

or his critique of the Vietnam War and correlation drawn between American militarism and the dangerously skewed nature of race relations in the deep south-

The absence of that missing star, thus, should be attributed to my personal aversion to factual inaccuracies, overused metaphors and bad analogies. Otherwise no rating system in existence can measure MLK's significance in American history and all that he stood for.

In a way this is Martin Luther's own account of the movement he helped steer in a direction which not only sought to free an entire community from socioeconomic and political servitude but prevented America from becoming synonymous with the ultimate hypocrisy of all - preaching the infallibility of human rights abroad (by waging wars against Communist totalitarianism) but carrying on with its tacit agenda of institutionalized discrimination back home.

"I am convinced that if we are to get on the right side of the world revolution, we as a nation must undergo a radical revolution of values. We must rapidly begin the shift from a thing-oriented society to a person-oriented society. When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights, are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism, and militarism are incapable of being conquered."

How the spirit of rebellion - which found expression for the first time with the Montgomery Bus Boycott in '55 (unwittingly started by Rosa Parks' act of denying her occupied seat to a white passenger) - trickled into the hearts of oppressed millions in Albany, Georgia, Birmingham, Alabama, Florida, Chicago, Boston, and Washington culminating in the passage of the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964, is recounted by King himself.

That aside, there's a brief autobiographical sketch patched together from the fragments of writings gathered from the Stanford University archive by Clayborne Carson. Excerpts from King's speeches (sometimes even the full text) also make appearances in between the accounts of all the non-violent movements of civil disobedience he gave leadership to.

To put it more accurately, this is less of an autobiography (since King didn't live long enough to write one) and more like a montage of every single written document or important oratory piece which King left behind. So lucidly written are these that Carson's work must have been reduced to simple editing and piecing together a coherent narrative out of the vast amount of material at her disposal.

And yet there are such glaring mistakes here which marred my reading experience. Consider this excerpt from King's personal writings after his visit to India in '59 which cemented his faith in the inviolability of civil disobedience as an effective tool to usher in socioeconomic and political change -

"On March 1 we had the privilege of spending at the Amniabad ashram and stood there at the point where Gandhi started his walk of 218 miles to a place called Bambi."

It's not Amniabad. In all probability, it's the Sabarmati ashram in Ahmedabad King is talking about, while the historic walk was to 'Dandi' - a coastal village in Gujarat (the state our present PM hails from). Not Bambi, the iconic Disney deer.

Even if it was a memory lapse on King's part or a sad apathy for geographical names, as a King scholar looking to publish a work of monumental importance Carson should have been more vigilant for inconsistencies such as the above, especially since Gandhi gets mentioned several times by virtue of his being King's role model.

(Some quick googling led me to the unhappy discovery that the Stanford archive still retains the unedited, therefore, incorrect information derived from the original sources. I can understand the significance of preserving King's writings exactly as he authored them but the insertion of incorrect facts diminishes the integrity of this work.)

Also occasionally 'Gandhi' is spelled as 'Ghandi'. (Aaarrrrggghhhhhh!)

In addition to these turn-offs, nearly all of King's speeches are so chock full of archetypal metaphor after metaphor that I felt it weakened the gravitas of the narrative. Perhaps, they would have been better off being included in shortened formats. The fact of God's mercy and benevolence being invoked (quite natural since King was a pastor) in every alternate sentence also served as an effective irritant. These are undoubtedly the primary reasons why it took me a whole month to finish reading this.

But these causes of botheration aside, there's plenty of good to be found in this compilation. Like the way MLK expresses his disappointment with 20th century capitalism in a letter addressed to his wife, Coretta -

"...I am not so opposed to capitalism that I have failed to see its relative merits. It started out with a noble and high motive, viz., to block the trade monopolies of the nobles, but like most human systems it fell victim to the very thing it was revolting against. So today capitalism has out-lived its usefulness. It has brought about a system that takes necessities from the masses to give luxuries to the classes."

or his critique of the Vietnam War and correlation drawn between American militarism and the dangerously skewed nature of race relations in the deep south-

"I do not believe our nation can be a moral leader of justice, equality, and democracy if it is trapped in the role of a self-appointed world policeman."

The absence of that missing star, thus, should be attributed to my personal aversion to factual inaccuracies, overused metaphors and bad analogies. Otherwise no rating system in existence can measure MLK's significance in American history and all that he stood for.